I am angry. I am really angry. I am so angry I can barely go to the lavatory. I am fuming. I don't think I’ve ever been crosser. If you poured boiling jam down the back of my neck, set fire to my trousers, defecated on the back seat of my car and forced me to stare without blinking at the pic of myself that accompanies this article, I couldn't be more furious. Hopping mad about sums it up. The reason for my ungovernable fury is simple to relate.

I’ve lost my sock. The one I had intended to put on this morning. Its twin languishes alone on the floor of my bedroom, denied the awesome privilege of sheathing my right foot because of the immortal cheek of its wayward brother. I’ve had to find another pair. To put the lid on the whole sorry business, I spilt coffee beans all over the kitchen floor. These two appalling catastrophes have combined to push my blood pressure up so high that there is some danger of my sustaining a severe nosebleed.

Now, yes. Of course. I would be among the first to concede that in the cool, clear light of reason, there is nothing bowel-shatteringly catastrophic about these two incidents. I dare swear that in a day or two, I will have forgotten all about them. Well, give it a week. What is so infuriating is the fact that I can be so volcanically incensed by two such nugatory, not to say insignificant, hiccoughs in the life of one who, generally speaking, doesn’t have too much to moan about.

I have a horrid feeling that I could never, ever, in my life be more angry about anything than I was fifteen minutes ago when I ransacked my room in search of this blasted benighted god-forsaken bloody bastard sock, which even as I write is probably laughing itself sick behind the wainscotting or wherever it is that the foul thing has chosen to hide. And surely that just won’t do.

I read, as is fashionable, my share of books on brain science, neuropsychology and whatnot, yet I don’t recall encountering anyone in the field touching on this point. A human being has, unless I’m vastly mistaken, only a certain amount of choler to expend. So discharging it all on errant ankle-wear surely cannot be right? Whatever strange moral, ethical or evolutionary purpose anger was designed to serve, getting splenetic about socks can’t be said to come anywhere near the top of the list. Yet I swear that if you were to attach an irometer or crossness sensor to my brain, its needle would shoot straight to the line where the dial reads ‘Danger. Extreme Overload. Evacuate’.

The same is true of happiness, of course. If I were left a billion pounds by an eccentric tycoon, asked to open the bowling for England, licked by a litter of Labrador cubs, and sat in front of a Columbo screening marathon, I should, of course, be madly, deliriously, absurdly happy. But not any happier than I was when, at the age of eleven, I discovered a ten-shilling note in the pocket of an old pair of shorts. Certainly no more ecstatic than when I was taken by my mother, aged six (me, that is, not my mother: she was significantly older), to the Bertram Mills Circus. I simply do not possess the capacity to feel any greater joy than that which lit me from within when Susan Maughan gave me her autograph after I’d seen her at the Britannia Pier, Yarmouth. She had a big hit with a song called ‘Bobby’s Girl’ that year. Those all set my needle to maximum happiness, which is to say no happiness could have exceeded those bursts of bliss.

Of course, a calculus of felicity raises Benthamite thoughts - tendencious territory today. For a very fine broadside against current cut-out-and-keep consequentialism, see the excellent Justin Smith Ruiu’s substack on the subject — and subscribe to him. I highly recommend it).

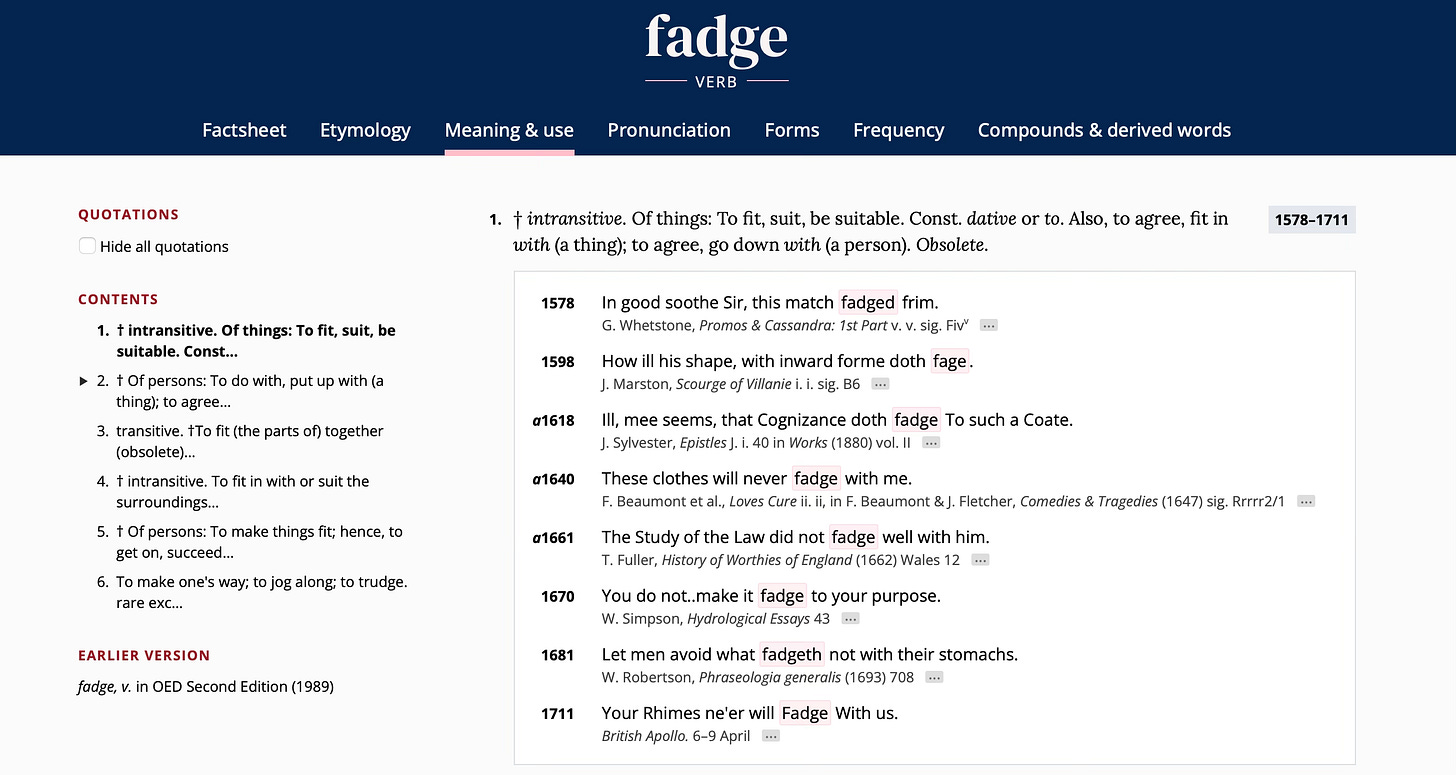

So what price the world? If I tremble with rage at a mislaid gentleman’s half-hose or wriggle with pleasure when a pop chanteuse writes her name on a ticket stub, what have I left in the emotion bank for genocidal injustice and violent cruelty? For the appropriate quanta of horror and disgust that should be directed at Israel’s behaviour, or Putin’s? It’s no good trying to imagine that those who suffer torture and cruelty and poverty feel exactly as if they've lost a sock, only it happens to be a very beautiful sock, with wonderful patterns and an attractive heel-panel, because that simply won’t fadge. These things aren’t “scaleable” as business types like to say loudly in hotel coffee lounges.

My worry is: are my anger and outrage accounts wiped out? Am I too overdrawn from using all my anger up on a sock to have any left to spend on worthier things? Oofh … as I type this out, it’s reminding me of something I read long ago. It’s nagging my brain. It’ll come to me.

To proceed: am I to assume that my life is so empty, my existence so vapid and barren, my mind so shallow, facile and unsympathetic, that the only event capable of engendering wrath in me is the loss of a small, foot-shaped tube of cotton? That really is a ghastly notion. If I thought it was true I would have to end it all. But what kind of a note could one leave behind? “Realised that my anger about the sock was unjustified and proved me valueless. If it is found amongst my effects, please have it stuffed and mounted and presented to the nation as a warning to others.” Not much of an epitaph, is it? But maybe that’s all I deserve.

I remember a man being interviewed outside the gigantic hills of flowers that were piled up against the railings of Buckingham Palace in August 1997. “My wife died of cancer two years ago,” he told the news cameras as he added his bouquet to the heap, “but I cried more when I heard the news of Princess Di.”

I was watching that with friends. How we scoffed. But then—possibly we were drunk or high or something like that—we began to admit that our emotions were just as curdled and confused. I confessed that I cried more when ET had to go home, leaving his friend Elliott behind, than at the death of Princess Di. And I wept more at the current TV ad for Hovis brown bread than for either of those.

Ah! I now remember what this “overdrawn at the bank of emotions” idea reminds me of.

E. M. Forster wrote an essay in 1926 called “Notes on the English Character”. At one point, he mentions a difference he has detected between English and Indian displays of emotion. His close Indian friend cried bitterly and almost inconsolably when Forster announced that he had to leave India and return to England. This highly emotional response left Forster feeling uncomfortable, embarrassed and rather cross. Seemed a bit of a carry-on for such a simple and necessary farewell.

I began by scolding my friend. I told him that he had been wrong to feel and display so much emotion upon so slight an occasion; that it was inappropriate. The word ‘inappropriate’ roused him to fury. ‘What?’ he cried. ‘Do you measure out your emotions as if they were potatoes?’ I did not like the simile of the potatoes, but after a moment’s reflection I said, ‘Yes, I do; and what’s more, I think I ought to. A small occasion demands a little emotion, just as a large occasion demands a great one. I would like my emotions to be appropriate. This may be measuring them like potatoes, but it is better than slopping them about like water from a pail, which is what you did.’ He did not like the simile of the pail. ‘ If those are your opinions, they part us forever,’ he cried, and left the room.

Oh dear. Well, Forster says that the friend soon came back in, offering the view that the point about emotions was not their quantity or intensity but their sincerity, their truth. What I suppose we would now call their “authenticity”. Forster declared himself “impressed” but nonetheless -

… I could not agree with it, and said that I valued emotion as much as he did, but used it differently; if I poured it out on small occasions I was afraid of having none left for the great ones, and of being bankrupt at the crises of life.1

Forster is fully alive to the awkward domains (banking and commerce) from which he draws his metaphor. To stay commercial for a moment myself and return to the case of that childish burst of illimitable happiness and the ten-shilling note (we’ll call it 50p for younger viewers) that I found in an old pair of shorts all those years ago: would I have been twice as happy if it had been a pound note, ten times happier had it been a fiver? And so on? On the other hand, suppose (as is to be hoped) that you love both parents equally: had one died, you would grieve deeply. If they both died, you might well, in fact, grieve twice as deeply. You are doubly bereft, your loss is double, so double the woe.

That’s odd: in those scenarios, joy seems harder to double than the emotion of desolation, even though the first is monetary and the second personal, spiritual, fundamental.

Nabokov in one of his novels, I’m damned if I can remember which, but have a thought that it might be one of the slightly lesser known and celebrated ones, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, perhaps, has a character who finds it strange that we can weep for an earthquake a thousand miles away that is reported in the morning bulletin we subscribe to, yet not for an earthquake that killed just as many, or maybe more, but which took place a thousand years ago and is described in a history book. In neither case can we do anything about them; in both cases, there is terrible human suffering at a distance, in one case a distance of miles, in the other, one of centuries. But it’s still suffering.

Of course, today, we feel we can do more. There are charitable disaster funds; we can draw the attention of the world to the world in ways unimaginable in the time of Nabokov’s novel. But still we have to face the thought that our anger, our sense of injustice, our sympathy, our revulsion, our outrage cannot be portioned out equally to each disaster, conflict, barbarous atrocity and so forth. We have to make a decision. We have to choose. Do we choose according to numbers? “I shall be most angry at the catastrophe that is causing the most death and suffering?” Do we listen to what we might romantically and sentimentally call “our hearts”? Do we expend the most emotional energy where we fancy we can most “make a difference?”

I suspect I have made some logical missteps along the way with all this. But it comes down to a strange, if obvious, fact about us. Our emotional wiring seems to be very good at responding to what happens directly, in real time, in physical proximity to our persons, in connection with our intimate or at least personal lives (can’t get closer than a sock). But as those connections grow more and more distant, outside our family circle, then outside our clan, community, tribe, country, continent, hemisphere … the signal attenuates, and our emotional antennae are less likely to quiver. I don’t claim this to be a shattering insight, by the way, I’m aware of how obvious it is. We suppose ourselves to have evolved to live in such groupings, and our bonding and emotional fields of force developed in those snugger environments. Nothing foudroyant about that,

But today, the weaker connections are boosted by the relays—akin to the “repeaters” that amplify a phone signal— of satellite and internet news, and of course, social media. So we are closer to the earthquakes, wars, atrocities and the thousand natural and unnatural shocks the earth is heir to. And our emotional antennae do quiver and encourage us to feel a keener emotional bond over distances.2

Information, knowledge - it rules now, as we know. But—aside from the limitless power given to data brokers and dealers and the dangers real or imagined of the nascent AI revolution—aside from all those threats that the ever-increasing mass and flow of information present, there is the simple threat that for each of us individually the burden of knowledge can become too heavy for our emotional response systems to bear. If all the noise in the world sounds in our heads we might end up with our palms pressed to our ears screaming, ‘Stop!’ before dropping dead of overload.

It is sentimental to think of all those people one has seen on one’s travels who know nothing of what is going on in the wider world and seem so much more content and cheerful than those of us whose daily practice on awakening is to reach for our phones and doom-scroll through the news until the adrenalin and cortisol have done their thing, and we are miserably unready for the day.

Aside from anything else, such unburdened people can shout guilt-free when they’ve mislaid something. If I lost a codpiece or buskin in medieval times, I might well roar with fury just as I do today when it’s a sock, but I wouldn’t damn myself for being insensitive and inappropriate because there was a humanitarian crisis unravelling in Ming China. Mostly because I wouldn’t know of the crisis.

I’m not arguing that we should ignore the monstrous horrors that afflict the planet and retreat into information-free shells that allow us to move guiltlessly in the world on account of our innocent freedom from knowledge. The genie is out of the bottle, and we know that what we know can’t be unknown.

My Kickstarter account will soon be offering the world a new device that might at least spread a little happiness closer to home. “The Fry Sock Caddy, available in executive green or boardroom burgundy and personalised with up to one of your initials. Two tough, weather-resistant, distressed leather trays that provide twenty-four hour, round the clock protection for your WiFi-tagged socks. We call it the The SockIt2Me.”

Thanks for popping by … until our next merry meeting, farewell.

“Notes on the English Character” collected in Abinger Harvest, E. M. Forster 1936. All of this is complicated by our knowledge today that the friend in question was certainly Forster’s lover. Nonetheless, the shape of what he says remains true even given the added complexity of interracial, same-sex relationships in those days.

Which, not very relevantly, is literally what telepathy means, ‘feeling over distance’ just as telephone is ‘sound over distance’.

Just yesterday I said in an interview that I "admire Stephen Fry because of his ability to remain unruffled ...etc, etc." ...I feel pretty silly now. I hadn't taken into account that you might sometimes lose a sock.

Hell hath no fury like a one-socked man. Diabolical things, socks! I once found one of mine clinging, SpiderMan-like, to the top of the dryer cylinder. My partner and I coined a word for such annoyances, which make one pig-biting mad but aren’t really so terrible in the vast cosmic scheme of things: kittenshit (it probably carries more gravitas in German). We invented this term when a tiny kitten that came with our guest cottage in Italy had explosive diarrhea in partner’s open suitcase. We swore and yelled and gnashed our teeth — until we both suddenly collapsed with laughter. We still use that term when something infuriating but not life-threatening rears its ugly head.