A strange thing it is to write about language, in language. As Alan Watts once said about something, it can seem like trying to bite your own teeth.

I was raised in the country—deep, deep, deep in the remotest countryside. You will barely be able to comprehend the depth and remoteness: the human settlement larger than a hutment lay a full twelve miles away from our house— a vast, unreachable distance that will astonish my American and Australian readers. Such is the size of the very well-named Great Britain.

So yes, very well. If the nice Substack people had such a thing, I would have been using the Irony font here. But to me, growing up, the thrumming, throbbing metropolitan Gomorrah that was Norwich did seem like the Three Sisters’ Moscow, more an unattainable symbol than a practical reality. Marooned in our little hamlet, I felt like the clergyman Sydney Smith, who, after his bishop moved him from a London parish to a rural rectory in Yorkshire, wrote ruefully to his friend Lady Holland that he was “… 12 miles from the nearest lemon.” I grew up twelve miles from the nearest library, cinema or coffee bar, let alone lemon. And twelve hundred miles from the nearest lemongrass.

Our family did have a television, black and white and with a snowy, fuzzy picture. Some older readers may remember the business of waving a wire attached to an antenna socket until the reception improved. In some families that I visited around the county, a junior member would have to stand in the sweet spot, holding the end of the wire for the full length of an important programme. If he or she moved and the picture wobbled or frizzed, they would be barked at horribly. In others, like ours, Blu Tack was used. Eventually, a wire coat hanger was stuck in the back (at some risk of electrocution) until, at last, on a bring and buy stall at a country fête, I happened upon a working rabbit ears antenna for 6d.

I know, I know, this is nostalgia corner at its least enthralling. I’m getting to the point, I promise.

One rainy afternoon, I was about, I don’t know 12 years old perhaps, I turned on the TV. A film had just started, five minutes in, so I didn’t catch the title. The moment I started to watch, I found myself becoming more and more transfixed. It was the language that engrossed me. The film was set in the past. I knew it wasn’t as old as Shakespeare or Jane Austen, but I couldn’t quite place the period. Very elegant and charming. But the talk. I had never heard anything like it. It made me want almost to dance. Me! Dancing! But there was something so joyfully perfect in its flights and formations. It was funny, too, incredibly funny. A new kind of funny. So elegant, so swiftly yet effortlessly delivered. The rhythm and patterning were divine. A whole new kind of music. At some point, a young man knelt in front of a young woman and said these words: “I hope I shall not offend you if I state quite frankly and openly that you seem to me to be in every way the visible personification of absolute perfection.”

It was as if I had been punched in the solar plexus. Lines of this dizzying splendour unrolled throughout. I wanted to jump through the screen and join these elegant, astonishing people with their perfect command of English, their easy but thrilling eloquence, and the sweet grace of their articulation, pulling perfect necklaces of words from their mouths. And a funniness, a comicality, the proper word for which I now know to be wit.

I sat on an uncushioned wooden kitchen chair, face flushed, mouth half-open, astonished at what I was hearing. I had simply no idea that language could do this. Language, that system you used to get the salt passed, to be given the correct time of day, to write thank you letters, to tell your family that you hate them and love them and couldn’t care less, to say sorry and thank you and please. It could dance and trip and tickle, cavort, swirl, beguile and seduce; its rhythms, subclauses, repetitions, colours and collisions were more than a match for music.

As soon as the film was over, I ran to the other side of the house.

“Mummy, mummy!” I cried. “I hope I shall not offend you if I state quite frankly and openly that you seem to me to be in every way the visible personification of absolute perfection.”

“Darling, what are you talking about?”

I explained what I had seen and heard and described the setting and the characters.

“Oh,” said my mother, “that must have been The Importance of Being Earnest.”

I wanted to know more. She added that it was by a certain Oscar Wilde and expressed the belief that there might be a copy of the play in the house, but I couldn’t find it. Never mind.

Despite being twelve miles from the nearest lemon, or perhaps because of it, the great county of Norfolk in those days sent out mobile libraries into the rural depths. Ours came every other Thursday to a meeting of lanes not far from the house.

The appointed day at the appointed hour, the grey pantechnicon rumbled into my fevered view. The driver stopped, climbed down onto the road, wheezed round to the side, opened a door, let down some steps and patted my bottom up and into the library. That was acceptable in those days. The librarian welcomed me aboard. She sat behind her counter, a sweet old thing in a lemon-coloured cardigan. She had soft, powdery cheeks and spectacles on a chain that rested on an ample bosom. A kind of fluffy Margaret Rutherford. Or actually a Dame May Whitty. Such people don’t seem to exist any more. They belong to a time when babies went in prams, not strollers, men had Brylcreemed hair and yellow nicotine-stained fingers, and women went shopping in hair curlers. Get on with it, Stephen.

“And what can we do for you, young man?”

“Well,” I said. “Might you have a copy of ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ by Oscar Wilde?”

She pointed, and there, sure enough, low on a shelf: “Oscar Wilde, The Four Comedies” A Woman of No Importance, An Ideal Husband, Lady Fandermere’s Wind and – heaven be praised – The Importance of Being Earnest.

She stamped the book out with that springy thump that is heard no more in the world, and I ran panting home, the book clutched to my heaving breast. I rushed upstairs, threw myself on the bed and began to read. For two weeks, I read that play every day, and the others, which I liked but not so much. It was The Importance to which I attached so much … well, importance. I learned it by heart. Truly.

What was it about that phrase that first triggered me? It is worth trying to drill a little deeper. “I hope I shall not offend you if I state quite frankly and openly that you seem to me to be in every way the visible personification of absolute perfection.”

… that springy thump that is heard no more in the world …

It’s elegant and beautifully balanced, but above all, it is funny. But why is it funny? At the risk of breaking a butterfly on a wheel or taking a spade to a soufflé, I think now that the line’s effect springs from philological roots that the listener instinctively understands without needing to know anything about etymology or diachronic linguistics and English’s mongrel mix of Romance and Germanic tongues. Somehow we just know without being told that declarations of love should be made using Anglo-Saxon words, because Anglo-Saxon is honest, it’s truthful, it can be trusted. We expect - “You’re so great. You’re the top. Be my bride. You stun me. You knock me for six. You’re my dream boat. May I kiss you? I want you for my own. I love you. Fuck me sideways, but you’re hot…”

But Wilde gives Algernon first, yes, a solid train of short Anglo-Saxon words, “you seem to me to be in every way…” but suddenly that train draws into a very Latinate station, “… the visible personification of absolute perfection.” If Algernon really meant it, if he were truthfully caught up in sincere feelings of love, surely he wouldn’t take time to express it like that; and yet, the very fact of being able to come up with so intricate a phrase is itself a loving compliment too. It’s a contradiction, like Dr Dolittle’s PushMe PullYou. It’s from both the heart and the head. I might say laughter fills the space between these contradictions or that laughter is a plucking on the overstretched strings of cognitive dissonance. I might say that, but then you might think me a poncy twazzock, so we’ll glide on.

“I hope I shall not offend you if I state quite frankly and openly that you seem to me to be in every way the visible personification of absolute perfection.”

In a strange way, the whole business of what’s Anglo-Saxon and what’s Latinate strikes at the heart of so much in English history. English the language, and English the people. Its history up until the last century at least.

On the one hand we have Robin Hood, Falstaff, Toby Belch — fair, Saxon yeoman bowmen, blue-eyed utterers of good Saxon oaths and flaxen-haired scoffers down of good Saxon cakes and ale. On the other, the Norman Sheriff of Nottingham, Guy of Gisborne, Malvolio - with their lank, black, greasy Severus Snape hair and their long, fancy, greasy words. Even Lydgate and Casaubon in Middlemarch reflect to some degree that same opposition, surely?

The story we tell ourselves, or perhaps more truthfully the story we used to tell ourselves right up through my childhood, feeds into this myth (and it is entirely a myth) – the Merrie England myth of solid hearts-of-oak Saxon honesty and directness, our valiant resistance to those puritanical, bureaucratic and corrupt Machiavellian Frenchies. Kind hearts and simple faith trumping coronets and Norman blood. The honest yew-wood longbow versus the cruel iron crossbow, the maypole versus the chain mail. You might even find a distorted, deluded descendant of this fantasy in the dreams of the blue-eyed British Brexiteer waving his true-blue passport in the pallid faces of those sneaky Eurovillains. (Having waited an extra two hours in the Non-EU queue for the privilege of doing so, of course).

But Normans were called Norman, we should recall, because Normandy was named after settlers from the north, Norse Vikings. They were far more likely to be blond and blue-eyed, frankly, than the Jutes, Celts, Angles and Saxons whose lands they conquered in 1066. But that myth remains a deep part of the vision we have of ourselves. Fancy words, intricate latinate constructions, such folderols and curlicues are deprecated by the plain-speaking British paragons - Robin Hood, Ivanhoe, Percy Blakeney, Hannay, Bulldog Drummond, Biggles and Bond.

There’s Winston Churchill, too. “We shall fight them on the beaches.” “Hitler can do his worst, we shall do our best”. His famous speeches are mostly compounded of punchy solid monosyllabic Anglo-Saxon. And then, for perfect, glorious effect, the odd Latinate phrase decorates the words like a heraldic scroll, as when on VE Day he preceded his triumphant barks of “Long live the cause of freedom. God save the King!” with the exquisite rumble of “Advance Britannia!” Those flourishes aside, Churchill’s famous saws and sayings are for the most part as Anglo-Saxon as Alfred the Great’s scorched cakes.

… the blue-eyed British Brexiteer waving his true-blue passport in the pallid faces of those sneaky Eurovillains.

So, yes, there’s a long tradition of distrusting Latin. “Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do,” Mark Twain advised. Disraeli said of Gladstone, “A sophistical rhetorician, inebriated with the exuberance of his own verbosity …” which has of course more than a touch of that consciously ironic Wildean self-contradiction, using sophistical rhetoric to condemn a sophistical rhetorician.

I have taken time over the story of that phrase from The Importance of Being Earnest and how it lit up so much excitement in me, because I am aware that I was extremely lucky to have had such an epiphany.

Two weeks after sucking all the juice I thought I could from Wilde’s comedies – the first three an apricot, a nectarine and a plum - the last, The Importance, a peach – I revisited the library van to return the book and asked Powdery Lady if she had any more by Wilde that I could read. I emerged carrying his “Complete Works”.

The inexpressibly moving and wonderful fairy tales for children (‘The Happy Prince’, ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’) and some of the short stories (‘Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime’ and ‘The Canterville Ghost’ for example) were easy and delicious enough to gulp down without effort; The Picture of Dorian Gray, was clever and haunting and seemed to come from the same tradition as Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, but with an extra touch of … I couldn’t quite place it. Essays such as ‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism’ and ‘The Decay of Lying’ were more than somewhat above me.

“A sophistical rhetorician, inebriated with the exuberance of his own verbosity.”

Two more weeks of furious reading passed, and I returned the great tome anxious to see if there was anything more by this marvellous being, this writer who could make words ring and sing like no one I had encountered before.

“Well, my darling, if this book you just returned says ‘The Complete Works’, then I fear there won’t be any more,’ Powdery Lady said, not without reason.

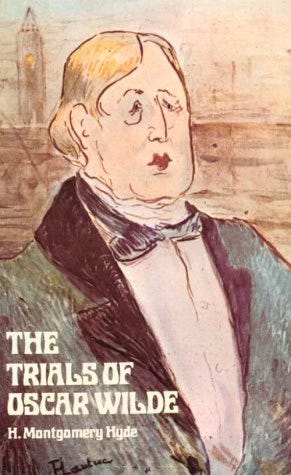

I flicked my way around the shelves, and then - in the biography section - I happened on a strange title - The Trials of Oscar Wilde, by one H. Montgomery Hyde. Mr. Hyde. ‘Trials’ struck me as an odd word, but perhaps this Oscar Wilde I admired so much had led a life of tribulation and hardship. It somehow seemed unlikely from his prose, but what did I know?

Back home in my bedroom, I embarked on Mr Hyde’s book. It was to change my life completely …

… to be continued

Part Two comes next week.

Thank you so much for looking in. Until our next merry meeting.

My god, I love you Stephen, I do. Why? Because you make me laugh – heartily. Because you make me think – broadly. Because you make me look up definitions (note to self: twazzock has been added to the vocabulary.)

We share an era (actually you are a mere month older than I) and I recall that “springy thump that is heard no more in the world” with nostalgia and a half smile. It goes hand-in-page with the excitement of finally being old enough to be allowed access to the “adult side” of the library along with the smell of oak tables and book binding glue.

I am an American with a body and head in the Colonies and a heart and sense of humor resident in the Green and Pleasant Land. I loved England the first time I spied the patchwork quilt of hedge rows through the plane window as it lowered itself into Heathrow. Well, really, my love affair began with the English language, British accent and self-deprecating wit that was piped into my Chicago childhood home via PBS (Public Broadcasting System) and, yes, rabbit ears! So smitten was I that I enrolled, at 42, as a mental health nursing student at the University of Nottingham (sans Robin Hood). Alas, plans didn’t work as I’d imagined and I returned to the States, but spent the next 25 years crossing The Pond as often as I could to visit, absorb and enjoy.

I haven’t been to England since 2020 at the height of Covid. I miss it, but I don’t miss getting there. For me, you evoke so many of the things I enjoy most about England. Best of all, I don’t have to fly or put up with twazzocks while I’m enjoying. I look forward to our next merry meeting.

Wonderful stuff, once again, and this time with a cliffhanger! I can’t help but think back to the infamous dinner where Wilde and Conan Doyle agreed to write pieces for an American magazine and the subsequent books that came out of that dinner: The Portrait of Dorian Gray and The Sign of Four respectively. It would seem Conan Doyle gifted Holmes with some Bohemian qualities that seem sure to have been inspired by Wilde, but I wonder if the slightly Gothic horror of Dorian Gray was inspired in part by the fog, gaslights, and hansom cabs of Holmes. We’ll probably never know but it seems to me that there was some cross pollination between the authors out of mutual respect and admiration. Certainly that dinner produced literary magic.